This article has been published with:What made 2025 different was not one dramatic announcement, but the way a series of interconnected reforms reshaped everyday economic life. Taxation, labour, energy, investment, and digital governance were not treated as isolated silos but as part of one system that ultimately affected how Indians earn, save, spend, work and power their homes.

What made 2025 different was not one dramatic announcement, but the way a series of interconnected reforms reshaped everyday economic life. Taxation, labour, energy, investment, and digital governance were not treated as isolated silos but as part of one system that ultimately affected how Indians earn, save, spend, work and power their homes.

The most visible impact has been felt by the middle class.

When Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman told a public gathering that the government would press ahead with deeper reforms, including a full overhaul of the customs duty structure, she wasn’t announcing just another policy tweak. She was signalling something more fundamental — that India’s reform strategy had moved from stealth to conviction.

Prime Minister Modi described 2025 as a ‘defining phase’ in India’s reform journey and urged investors to ‘keep trusting India and investing in our people.’ The phrase matters. This was not the language of crisis management or emergency repair. It was the language of long-term restructuring of a government increasingly willing to own its reform agenda openly rather than disguise it as technical housekeeping.

The new income tax framework delivered tangible relief, with salaried individuals effectively seeing breathing room of up to ₹12.75 lakh in annual income through exemptions and slabs. This was not symbolic; it showed up directly on salary slips, in household budgets, and in consumption patterns. More disposable income meant better household savings, stronger demand for goods and services, and rising confidence.

In economic terms, this was growth driven by confidence, not compulsion. The middle class was no longer treated merely as a tax base but repositioned as the engine of demand.

GST 2.0 continued this simplification logic. Rationalised slabs and clearer structures reduced disputes, increased predictability, and made consumer goods more affordable. The shift was from complexity to clarity and from opacity to trust.

Since 2014, around 25 crore Indians have moved out of poverty, forming what policymakers now call the “new middle class.” 2025 arguably marked the moment when policy finally began speaking directly to them.

For decades, labour reform in India was the political equivalent of a live wire — everyone agreed it needed fixing, but no one wanted to touch it. Successive governments avoided it because the costs were immediate, visible and politically painful, while the benefits were long-term. That political logic quietly changed this year.

Labour reform is where the government crossed its political Rubicon. Twenty-nine outdated labour laws were replaced with simplified codes. Gig and platform workers were formally recognised. Employers were offered a “one nation, one compliance” framework.

This wasn’t merely about making life easier for businesses. It sent a signal that India wants growth, but not jobless growth.

Manufacturing responded. Quarter after quarter, it grew steadily. Capacity utilisation rose. Logistics improved. Policy stability reduced risk. India began looking more like a manufacturing base, and the credit goes to structural conditions finally aligning.

Perhaps the most underrated reform of 2025 was the recent nuclear energy liberalisation. The opening up of atomic energy, including through the SHANTI Bill, was not cosmetic. It was about future-proofing India’s energy security. India cannot industrialise, urbanise, and digitise while burning coal indefinitely. Clean, stable base-load power is not a climate luxury; it is an economic necessity.

This reform recognised that energy security is national security.

Beneath the headline reforms sits an equally important transformation — India’s digital public infrastructure. Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, and DBT linkages have quietly rewired the state’s delivery capacity. Welfare now flows directly. Leakages have reduced. Administrative friction has fallen.

This is not ideological reform; it is an operational one, and arguably more powerful than any speech.

For all its achievements, 2025 still cannot be considered a complete miracle year, as challenges still persist.

The manufacturing sector has not translated into a larger share of overall GDP. Urban air quality remains dire. Smart cities still don’t feel very smart. Private investment remains cautious. Real wages have not quite surged. Employment growth has lagged behind output growth.

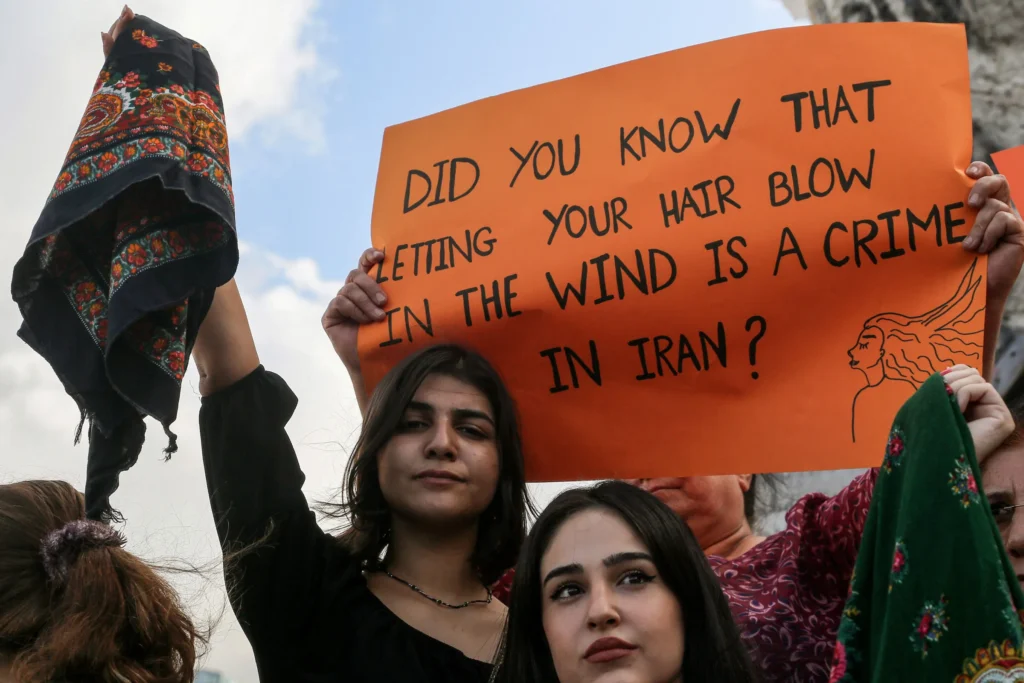

Most importantly, the government continues to avoid the most politically explosive reforms, such as land acquisition and agriculture. The farm laws collapse remains a reminder that structural reform still collides with social reality. Conviction exists, but it is selective.

Now, the governing mantra has been pragmatic: deliver public goods, incentivise participation, reduce political friction, invite private players, and avoid direct confrontation. It has produced stability and steady growth, but perhaps at the cost of deeper transformation.

So, has India pivoted from stealth to conviction? Yes, but within boundaries.

The state now openly owns its reform agenda. It is less defensive about being pro-business. It is more confident about structural change. It is more willing to talk about productivity. However, it remains cautious about reforms that provoke social rupture.

This is not necessarily a flaw. It may be India’s version of reform realism.

Now the real question is whether India is ready to extend that conviction to the reforms it still fears, and whether political courage can eventually match economic ambition. That will decide whether this was a chapter — or the beginning of a longer story.